Nuclear Paradise Lost

By David Kattenburg

Several dozen scientists, technicians and military officers, in the closing days of World War Two, were the first humans to witness an atomic explosion—the first to see what an atomic bomb could do

The people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were the first and only ones to experience an atomic blast in the flesh. Bikinians were the first to be driven into exile—to be dispossessed—so that nukes could be tested on the lands and waters they called home, in the name of peace and freedom.

Admiral Ben Wyatt offered comfort to Bikini’s 167 men, women and children, gathered in front of their humble little church in February 1946. Their evacuation was being carried out “for the good of mankind, and to end all world wars,” Wyatt assured them, to which Bikinian King Juda replied—so the story goes: “Everything is in the hands of God.”

Of course, the lives of King Juda and his people were now in the hands of the U.S. military and Department of Energy. Their exile would be of biblical proportions—an exodus that would first take them to the little atoll of Rongerik, 125 miles east of Bikini; a sixth of Bikini’s size, with hardly any food or water. The U.S. gave them enough provisions for a couple of weeks. Soon the Bikinians were hungry, with nothing to eat but poisonous fish. They pleaded to be removed. In late July 1946, King Juda traveled back to Bikini with the Americans to view the second of two atomic tests, codenamed “Baker.” Like the June 30 “Able” device—dropped from an airplane—“Baker” was a 21-kiloton bomb, the same size as “Fat Man,” that devastated Nagasaki. Amid growing rivalry over at the Pentagon, Operation “Baker” would be the U.S. Navy’s turn to try out a nuke of its own, so the bomb was detonated beneath the surface of Bikini Lagoon, in order to sink a few ships.

Upon his return to Rongerik, King Juda reported to his people that Bikini looked the same. Still, they would not be going home. As winter closed in on tiny Rongerik, starvation grew. Visitors from the U.S. were shocked, but Washington had more pressing issues to deal with: convincing the U.N. to turn the Marshall Islands into a “Strategic Trusteeship,” with the U.S. in charge. The U.N. obliged—the only such arrangement ever to be granted by the international body. As Trustee, the U.S. would be responsible for promoting Marshallese “economic advancement and self-sufficiency,” and for protecting the Marshallese people “against the loss of their lands and resources…” The absurd contradiction between such high-minded aims and the U.S.’s actual activities in the middle of the Pacific aroused indignation among influential editorialists. The Truman Administration scrambled for a solution. In late 1947, U.S. navy personnel took a crew of Bikinians to tiny Ujelang Atoll, in the far northwestern Marshalls, to help build houses for their people. Having built these, U.S. Trust Authorities then decided that the new houses would best be occupied, instead, by the people of Enewetak Atoll, soon to be evacuated for “Operation Sandstone,” involving three nukes dropped from towers.

In March 1948, 184 malnourished Bikinians were shipped from Rongerik to the U.S. base on Kwajalein Island, in the central Marshalls, where they were housed in tents beside a runway. In November, after much discussion, they were moved once again, this time to tiny Kili Island, thirty miles south of Jaluit, on the southern end of the Ralik Chain. Kili was just an island, without a lagoon, so Bikinians could no longer fish the way they once did, in calm, protected, bountiful waters. Starvation ensued. A ship from nearby Jaluit got wrecked while trying to deliver copra and other fruit. Food had to be airdropped. In 1955 and 1956, inability to deliver food in rough seas led to food shortages. The U.S. proposed that some of the Bikinians move to Jaluit, where the fruit was. Some went. Most of them remained on Kili. One can imagine how the Bikinians must have felt; shanghaied on this barren speck of coral, dreaming of the day they would go home.

Unbeknownst to Kili’s wandering Bikinians, their lovely home had been transformed. The U.S. had been setting off bombs there with great abandon. The six-shot “Castle” series, between February 28 and May 13, 1954, had featured some of the most powerful H-bombs in the Pentagon’s arsenal. Five of these had been tested at Bikini. The biggest—the 15-megaton “Bravo” shot inaugurating “Castle” (often referred to in U.S. time: March 1, 1954)—ended up vaporizing several of Bikini’s northern islets, showering radioactive fallout all over the northern Marshalls (Tritium from Bravo would actually be detected as far away as Canada and Europe). The seventeen-shot “Redwing” series had followed—eleven blasts at Enewetak and six at Bikini—and then the 33-shot “Hardtack” series, beginning in late April 1958, involving lots of bombs set off on barges. With global peace and security hanging in the balance, U.S. Trust authorities talked the Bikinians into signing a new agreement, this time handing full rights over their atoll to the Americans. In exchange, the Bikinians would receive permanent title over Kili and Jaluit, plus about $325,000. King Juda signed the deal without legal advice.

By now the Bikinians had grown accustomed to life on Kili—battered by typhoons; blocked from fishing waters by enormous waves. Unable to catch wonderful rainbow runners, or grow their traditional foods, Bikinians ate canned food generously provided by U.S. Trust authorities. Diabetes and heart disease—the pathologies of cultural assimilation—grew prevalent. In the mid 1960s, talk emerged about letting Kili’s 540 Bikinians residents go home. Radiation levels had waned, U.S. investigators concluded, and would not pose a health hazard. President Lyndon Johnson urged that the return be staged “with all possible dispatch,” so a plan was concocted to remove radioactive debris from Bikini, then replant vegetation and build houses. But as the cleanup moved forward, scientists were disturbed by lingering radiation. In spite of forebodings, the first group of cautious Bikinians returned to their atoll in 1972. Others soon followed.

Joyous homecoming soon turned to debacle. In June 1975, health physicists observed elevated radioisotope levels in the Bikinians’ blood and urine. Their staple fruits, coconut, breadfruit and pandanus, were clearly too contaminated to eat. Coconut crabs—popular among the Marshallese—were inedible too. The crabs had been consuming their own radioisotope-contaminated shells. It was at this stage that the people of Bikini filed their first lawsuit, demanding that U.S. authorities carry out a definitive radiological assessment across the entire northern Marshalls. An aerial survey would be conducted later that year, but initial enthusiasm for resettlement had been poisoned, along with the Bikini’s traditional diet. Back to barren Kili, Ejit and Majuro, the Bikinians went.

As Bikini’s nuclear exiles wandered the ocean wilderness, the people of Enewetak Atoll watched and undertook actions of their own. They had been living on Ujelang Atoll since December 1947. In October 1980, five hundred of them resettled three of Enewetak’s southern islands—Medren, Japtan and Enewetak Islands—that the U.S. had cleaned up. Tiny but previously inhabited Enjebi Island, on the atoll’s northern end, where ten nukes had been detonated, was still too contaminated to resettle, though. Runit Island, on the eastern side of the atoll, would also be off bounds. There, beneath a giant concrete dome, sat 73,000 cubic meters of radioactive soil and debris poisoned in a flurry of two dozen U.S. atomic tests carried out in the spring and summer of 1958, aimed at beating out the clock before a moratorium on atmospheric testing came into force.

Within months of their 1980 homecoming, amidst complaints over food shortages and fear of radiation, a hundred Enewetakers returned to Ujelang. Still, the resettlement held fast. In 2001, a radiological laboratory was set up on Enewetak, equipped with a whole body counter to measure how much radiation settlers were absorbing into their bodies. Ironically, diabetes, heart disease and other “lifestyle” disorders associated with the consumption of canned and processed foods from the U.S. would pose a greater health hazard to Enewetakers than lingering radioactive fallout.

Meanwhile, little Rongelap Atoll also struggled to be reborn. On February 28, 1954 (March 1, 1954, by North American timekeeping), sixty-four Rongelapese men, women and children had been rained upon by “Castle Bravo.” The fifteen-megaton blast on the northwest corner of Bikini Atoll had vaporized several islands, sending a dark column of radioactive coral particles and dust rocketing into the upper stratosphere. Winds had shifted just prior to the test, and radioactive fallout soon began drifting down on nearby Rongelap, Ailinginae, Rongerik and Utrik atolls. Having received no warnings, the Rongelapese waded through ankle deep ashes, tasted them and drank contaminated water. Acute radioactive burns, vomiting and hair loss soon followed. Historians continue to debate whether or not senior U.S. Trust authorities actually knew, in advance, that this would happen; whether their three-day wait before evacuating Rongelap’s residents was intentional (unwitting American servicemen, it should be noted, were also exposed to the fallout). They moved Rongelap’s people to Kwajalein Atoll, for medical treatment, and from Kwajalein to tiny Ejit Island, on Majuro Atoll.

In 1957, thinking Rongelap was now safe, U.S. Trust authorities moved the Rongelapese back again. “The habitation of these people on Rongelap Island,” one scientific study noted frankly at the time, “affords the opportunity for a most valuable ecological radiation study on human beings.” Almost immediately, their bodies began absorbing plutonium and other radionuclides and the Rongelapese were evacuated once more—this time to Mejatto Island, on Kwajalein Atoll. A second homecoming wouldn’t be contemplated until 1985. Two years later, radioisotopes seeping into their tissues and blood, the Rongelapese evacuated themselves back to Mejatto.

It would take the Americans another decade to figure out how best to safely resettle Rongelap. The U.S. Congress’ Rongelap Resettlement Act led to a 1998 “Phase I Resettlement Program.” A year later, the U.S. Department of Energy, Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI) and Rongelap Atoll Local Government agreed to kick off Rongelap’s resettlement. The Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory was tasked with assessing the atoll’s remediation and quantifying resettlement worker exposures. By 2001, remediation and infrastructure re-development were complete. Workers had replaced habitation area soils with clean, crushed coral, and agricultural fields had been fertilized with potassium, which out-competes radioactive cesium-137 for crop uptake. Freshwater and electrical supply systems had been built too, along with a paved runway, a concrete pier, a few tourist bungalows, a field station, and a health physics lab equipped with a whole-body radiation counter. In 2001 and 2006, gamma radiation monitoring surveys of Rongelap’s new community area were conducted. According to the Marshall Islands Dose Assessment and Radioecology Program—a program of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory—“the results of these studies clearly show that the combination of limited soil removal and addition of crushed coral fill is very effective in reducing external gamma exposure rates.” Today, little Rongelap Atoll—61 islets spread out over three square miles, around a 388 square-mile lagoon in the middle of the Pacific—is now officially open to well-heeled pleasure yachtsmen and eco-tourists from around the world.

It’s a huge irony. Rongelap’s nuclear poisoning almost sixty years ago has ensured that, once short-lived, brutally powerful gamma emitters burned themselves off—and other radionuclides cycled through the environment and were washed into the ocean—the atoll would emerge ecologically pristine. Her coral reefs are reportedly dazzling. Under the leadership of the atoll’s inspired and energetic major, James Matayoshi, Rongelap Atoll Local Government Council has now launched the Rongelap Atoll Beach Resort. Visitors are invited to go diving, fishing, “eco-cruising,” and “luxury kayaking” here. Those who prefer solitude can go for long strolls down beaches of fine, hot sand, or simply relax and read on the deck of a rustic bungalow. At night, locally produced pork and other produce may well be on the menu. Rongelap’s resurrected economy will be further boosted through the sale of locally grown black pearls. Black lip pearl oysters recently yielded a $20,000 harvest for Rongelap, and mayor Matayoshi hopes the project can be scaled up.

With economic opportunities such as these in place, Matayoshi and his local government council are hoping that the bravest of Rongelap’s 400-strong community on Mejatto Island will begin moving home. A local Rongelap contractor has been hired to build five houses. Forty houses are projected to be complete by December 2011.

Cynical Marshallese observers scoff at Rongelap’s resettlement and economic development plans. No one else has pulled off anything like this. Why should little Rongelap? At the top of their list of challenges is the collapse of the RMI’s national airline, Air Marshall Islands (referred to by some as “Air Maybe”.) Since the last of AMI’s small commuter planes ceased to function in 2007, and the operation went belly-up, far-flung atolls like Rongelap, Bikini and Enewetak have become more isolated than ever. In the absence of a reliable airline, the economic and logistical constraints of re-populating the Marshalls’ northern atolls and supporting tourist operations will be enormous.

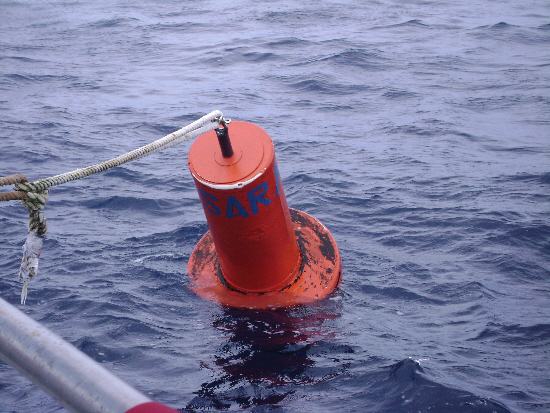

A similar project of Bikini Atoll’s foundered for precisely this reason. In the early 1990s, Bikini’s leadership on Majuro came up with the idea of launching a dive operation. Dozens of U.S. naval craft were sitting on the bottom of Bikini Lagoon. They had even been moored and marked with buoys, by U.S. authorities engaged in the island’s cleanup. “Tech” divers from around the world would pay big bucks to explore some of the most outstanding naval wrecks on the planet, including the world’s largest sunken aircraft carrier, the illustrious Saratoga — affectionately referred to as “Sara” — and the Japanese imperial flagship Nagato, where the Pearl Harbour attack was launched and Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto received the coded triumphal message—“Tora! Tora! Tora!” Income from the dive operation would provide an economic springboard for Bikini’s resettlement.

Technicians and scientists from the U.S. Department of Energy—supported by a handful of Bikinians—had laid the groundwork. They cleaned up southern Eneu Island, paved a runway and put up a few buildings. Neighbouring Bikini Island, where most people lived prior to nuclear testing, was next. The navy wrecks on the bottom of the lagoon soon drew the Americans’ attention. Military historians, marine archaeologists, and health physics researchers came and went. In June 1996, Bikini Atoll Divers was launched. Soon, the operation was generating cash (albeit with subsidies from the Bikini-Kili-Ejit Local Government Council). But in September 2007, the last of Air Marshall Islands’ commuter aircraft ceased to function—leaving a half dozen “tech” divers and one journalist stranded on lovely Bikini Island for an extra week (listen to the audio link at the top of this article). In 2008, Bikini Local Government Council closed Bikini Island for tourism (although wealthy, self-contained yachtsmen are still permitted to visit the atoll).

The demise of Bikini Atoll Divers has cast a gloom over Bikini’s resettlement prospects. U.S. authorities insist that Bikini can be safely repopulated, following a similar path as Rongelap. Bikinians are doubtful. They’re not convinced that a Rongelap-style scrape and coral replacement, accompanied by potassium fertilization in the fields, is sufficient. They want all contaminated soil to be removed, followed by a cleanup of the remaining 22 islands in their atoll. U.S. authorities argue that a full scrape and soil replacement would be prohibitively expensive, and might fatally compromise the island’s already limited fertility. Bikinians haven’t the money to do it themselves. Their Resettlement Trust Fund is currently valued at $80 million. Having slashed operational budgets for their local governments on Kili, Majuro and Ejit, in the wake of huge losses in the value of their investment funds, Bikinians haven’t the cash to provide basic health care and electricity to their 4,500-strong community-in-exile, let alone finance such an extensive cleanup. Frustration is enormous. “The Bikinians feel like they have done nothing wrong yet they are being punished, while they see the U.S. printing money to save their own,” says Bikini liaison officer Jack Niedenthal.

And so, Bikinians continue to live in diaspora on barren Kili Island, on Majuro atoll’s Ejit, and in the crowded capital of Majuro itself. Like many fellow islanders, King Juda’s people and their descendents suffer the ills of cultural alienation: diabetes, hypertension, alcoholism, sexually transmitted disease, domestic violence, and suicide. Perversely, U.S. compensation for past nuclear wrongs has arguably wreaked the most grievous damage. Naturally self-reliant islanders find it difficult looking after themselves—the precise opposite situation from what America was mandated to achieve in 1946. Today, Compact funds outstrip productive investment and tax revenues two to one. Islanders live off U.S. dollars and regard themselves as victims. Some complain when told they don’t have a tumour, because that means no cash. Those that do receive compensation are scorned as rich. Informed, intelligent Marshallese commentators struggle to come to grips with an August 2010 scientific study predicting that the U.S.’s 67 nuclear tests at Bikini and Enewetak will eventually lead to a total of 170 “excess cancers” among those alive at the time—rather than five hundred, as predicted by the National Cancer Institute in 2004.

Fortunately, the Marshallese are aware of all this. “And why is the U.S. obligated to fix Majuro?” asked one local commentator, in the course of a recent debate at the on-line Marshallese website yokwe.net. The discussion thread centered around the latest Land Use Agreement (LUA) demand by Kwajalein Atoll chiefs that the U.S. pay $570 million to continue using Kwaj as a bulls-eye for ballistic missiles. “They could take 5 billion and solve the whole issue with the LUA and even give RMI a nice chunk to fix Majuro too,” one person had suggested. “Gimme, gimme, gimme,” another retorted. “Where does it all end? The US never agreed to support the RMI in perpetuity.”

Shaking off sixty years of dependency is much more than just talk in the Marshalls these days. Rongelap Mayor James Matayoshi is spearheading his atoll’s resettlement. Young Majuro activist and entrepreneur Ben Chutaro is encouraging the overcrowded Majuro neighborhood of Jenrok to clean up, create jobs and earn cash for healthy community projects through the sale of its recyclables in U.S. markets. Chutaro, Matayoshi, and others of their generation are what make the Marshalls exciting. They want justice from the U.S., but are mostly concerned about moving the Marshalls forward, shedding its “victim mentality” and getting off U.S. “welfare.” After years of injury and hardship, it’s people like these – not gorgeous beaches – that make the place so remarkable.![]()

This is an interesting artilce. I. like many Marshallese who live within the 250 miles radius of Rongelap Atoll, we are extremely concern that the residents of Rongelap are being forced to move back to Rongelap. Too many times, the United States have lied to the Marshallese people. While much U.S. money has been poured into the ROngelap Atoll Local Government, this is dollar diplomacy, only carried out to silence the ROngelap Council. How sad!

Wake up Marshallese. There is a forocious and hungry wolf amongst our people. It’s better we starve than the U.S. Government to exterminate us ever so slowly and painfully. Wake up!

[…] good date, atmospheric nuclear tests going great guns at Bikini Atoll, in the central Pacific, as well as in the Nevada desert, spewing radioactive debris into the stratosphere and around the […]

[…] Atoll, in the central Pacific, is as desolate as a place can be. Here, between 1946 and 1958, the US military carried out 23 nuclear tests. The largest, a 15-megatonne thermonuclear blast codenamed “Bravo,” in March 1954, vaporized […]

[…] US military nuclear testing site. At the time, residents were relocated to nearby Rongerik and Kwajalein atolls before arriving at Kili Island in […]